Bloodrites

Our end tumbling backwards, our linebackers attacking blockers, I sprinted forward to tackle the plunging fullback. He pumped his thighs and tried to veer away but I lowered my shoulder, aimed my helmet at his crotch, and began to clamp my arms even before we collided.

I remember only the impact.

Sometime later, mouth filled with blood, I gazed into the concerned face of Brother Justin, our assistant coach, who knelt over me as though offering dreamy benediction. I was fourteen years old, playing high school football on a championship lightweight team, but this attention was new. I vaguely noted one teammate about my age who looked down at my face, then quickly avert his eyes. "Jesus," he gasped.

An ice bag was placed on my broken nose. "Can you stand up?" asked Justin, whose own beak featured the tell-tale swoop of a healed fracture.

"I think so." The middle of my face was numb and my vision was still blurred, but I planted first one leg, then the other, under me and swayed there, tasting a great gulp of my own salty self before spitting it up — the first freshman blooded on that field.

I hung there for a long moment — willow slim, my whiskerless face sheeted with blood — suspended between childhood and what would follow, then Tom Dugger, our head coach, his eyes shining, grabbed my shoulder pads and said for the entire team to hear, "Good hit!"

Childhood slipped from me like a cocoon, and the other players, even the bewhiskered juniors and seniors who had stood back and grinned at my injury, surrounded me: "Yeah, Has', good hit! You drilled him, man."

If so, I didn't remember it. It had, in any case, been only a intrasquad scrimmage and I had long since become a starter at safety when, inserted to replace an injured upper-classman during our first game of the season, I had managed three tackles in three plays — opponents seeming to drift directly into my arms. Now, however, tasting my blood and savoring that intonation — "Good hit!" — I had become more, a warrior, and I would with fits and starts, remain one, tasting my own blood many times and not always on the field, because I learned that there were worse fates than physical injury.

Years later, I was inducted into the U.S Army, coasted through basic then advanced infantry training, and when I returned home on my first leave, my pals asked me how tough it was. I answered honestly: "Compared to two-a-day practices in August, it wasn't." Ironically, only major combat I ever saw as a soldier — and I in no way equate such mild pounding with the horrors of modern warfare—was on the gridiron for I played football there too. I experience no guilt over not having fought a war because when drafted I went, and I would have gone anywhere assigned. As it turned out, I was assigned to a football field.

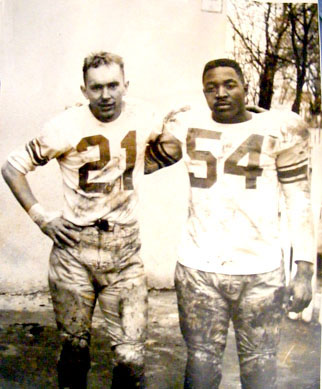

On the wall of my office today hangs a photograph taken in Wurzburg, West Germany on Thanksgiving Day in 1959. Slender as a song leader, I stand arm-in-arm with a muscular black man from Mississippi named Richmond Barber, who was my best friend on the team. We appear exhausted. The front of my jersey and pants are stained with blood from my much-broken nose and a dazed grin plays across my face. Rich is more somber, his eyes hooded. We had both just played the final football games of our lives and we had significantly contributed to a win, 7-0, over a better team.

There is also a certain defiance in that photograph. Racism was rampant among American soldiers in Europe then, and at Mainz a black teammate and I were physically attacked by white G.I.'s at a restaurant for the crime of dining together. Ironically, a Mexican-American soldier, whom we didn't know, came to our rescue. Even then, though, on the field we were as good as our performances: football allowed us more equality that American society at that time encouraged. Rich and I were equals on the field and would forever remain equals off it. The pragmatic egalitarianism of a warrior's urge for victory precluded racism.

There are, of course, many negative things to be said about the excesses of football. It is closely linked to sexuality and it often encourages crudity. It is dangerous of course, but that titillating edge is necessary for emerging warriors. Some people overvalue the sport: it is not the world; it is not as important as curing cancer or feeding the hungry. Does it build character as some coaches claim? It can, but as far as I've been able to observe, athletes by no means automatically become better citizens than non-athletes. And football can certainly build arrogance.

On the other hand, it is fun, featuring rough male joshing that constantly tests one's ability to take it: red-hot liniment in a guy's jock strap was on common prank; a teammate of mine had a pair of sweat-sox that he swore brought luck, so we substituted a pair of mine without telling him — same luck; freshmen at my high school were told that a jock cup was a nose guard and shown how to wear it on their faces.

It doesn't stop at high school. Hampton Hurt's first pre-game meal at New Mexico State became vegetarian when his teammates stole his steak; it remains missing to this day. Dave Blanchard, who played at Sacramento State, recalls a teammate with a permanent limp who took constant teasing and who retaliated by walking with his short leg up on a curb to imitate his non-limping teammates. When Jim Houston was a scholarship freshman at Abilene Christian, he was flattened in practice by an upper classman, who was in turn remonstrated by the coach: "We got some money invested in this boy, Buster. We'd like him to last at least halfway through the season." Like life itself, football is tough and you learn how to take it or else. A backfield coach once constructively critiqued my play thus: "Pick them legs up, Haslam. You run about as good as old folks screw."

Such incidents mask the fact that football really can serve a thaumaturgical purpose in a desacralized society like ours, allowing young males ceremonies that lead them toward manhood. For an only child like me, raised by a mother who hated and sought to suppress male urges, the masculine rituals of controlled violence offered what I believe was a biologically necessary outlet for one of testosterone's dual urges. Everything from the smell of the training room to running the gauntlet in practice or going nose-to-nose in the pit, everything from the ceremonial taping of ankles and wrists to the prayer before a game conspired to move an apprentice warrior away from one world toward another where deep biological urges can be channeled, validated, released. Life wasn't supposed to be easy and on that field, for me, anyway, it wasn't.

Culture consists of forms that allow us to live meaningfully. Such patterns are vital since they link us with those who preceded us, but they are not unassailable. In fact, we show our respect by challenging and sharpening tribal forms. As a cultural cipher, even in some high schools, football has become too much business, too much a steroid freak show attended by uninitiated dreamers who've never tasted their own blood. Spectator sports, to the extent they are merely the domain of fans, offer corrupt rituals. Only initiates can appreciate the empowerment to uncertain young men offered by controlled warfare.

And participants should be the first to recognize excesses. I have long believed that males — biologically inferior to females in so many ways — have been granted peacock tails, the illusion of grandeur, in many societies as compensation for biological limitations. The sort of short-lived breeding and fighting and working that men have been evolved to do is vital, more vital than we are as individuals, but women have a deeper responsibilities. I do not believe that traditional sexual roles developed as the result of injustice, but that injustice toward women as well as others has certainly become as fixture in them. Problems are compounded because overpopulation has gradually diminished the prestige of motherhood, traditionally the most important of vocations.

In our society, not only has the peacock's tail not only outgrown his body, as unequal pay for equal work and the closed doors of the old-boy network so amply illustrates, but it has overcompensatorily led to denials that maleness itself is justifiable. We need to "feminize" ourselves, I have been told, to soften. Fair enough, but essential maleness has more to do with genetics and chemistry than with society, so I'll gratefully hug my buddies with greater ease than before, but I'll also try to stomp the pee-wadding out of anyone who really wants trouble, man or woman, and I had better be willing to do that or a jillion years of evolution don't amount to beans. I'm far more interested in being a man who is sensitive than one of those "Sensitive Males" who wishes he was a woman.

Two of my sons and both of my daughters have been athletes. None of them played football and none took any heat from me. If one of my girls had wanted to, I'd've said yes, by all means, but I'd've also said that no she could receive no special treatment, pro or con. There have been "masculine" women and "feminine" men — and everything in between — since the beginning of time and in a free society everyone had damn sure better be allowed to pursue their own fulfillments.

But I can understand why coaches resist men on women's teams and vice-versa; demands for such integration represent ignorant extremes of egalitarianism the confusion of similarity and equality. Recent studies in sociobiology — most of them conducted by female-male teams, interestingly enough — offer convincing evidence that females and males are essentially different, designed by nature for special, not fully understood roles. Sports such football offer males one avenue to fulfil part of their biological heritage, so resistance to total sexual integration may not be sexist at all. There is, after all, nothing wrong with the existence of institutions clubs, or associations in which only women or only men assemble to work out their peculiar humanity, whether menstruation lodges or sweat houses. For me, high-school football fulfilled the latter function: a warrior quest in an all-male environment.

I was by no means a star in high school or at any other level, but was what the British call a "useful" player. No, having seen future college and professional standouts like Frank Gifford, Jeff Seimen, Joey Hernandez, Jimmy Maples and Curtis Hill cavort on local gridirons, I never harbored the illusion that I was an outstanding performer. But I played: I showed up, pulled on my pads and did what was asked of me. And I suffered some distinct humiliations that were, in their own way, educational.

As a bench-warmer in college, I believed that the coach would one day come to his senses and insert me into a game where I would, of course, save the day. Midway through the season of 1957, I had seen only spot duty running back punts and kickoffs, plus a few minutes as a designated deep defender. Then, in the midst of a close game, the coach Johnny Baker called my name: "Haslam!" I leaped to my feet, sprinted to him as I fumbled with my helmet, and he said, "Give me your jersey. Leroy tore his and we forgot the extras." Under floodlights in front of 20,000 people, my shirt was stripped and, while my teammates did their best to shield me from view, one more layer of illusion came off with that green-and-gold jersey. I lived through it.

Lights also shone the night I suffered my most troubling injury. In 1954, playing for the league championship in my final high-school game, I was tackled by the last defender as I darted through North High's secondary. The play remains kaleidoscopic in memory: cartwheeled into the air by a sharp collision, a flash of stadium lights as I flew, bouncing on the turf but clinging to the ball; I heard the whistle, the crowd's roar as my tumble slowed and I prepared to brace myself and rise. But a deep, unexpected impact interrupted me, an impact that sucked my mind into my bowels where imploding fire curled my body.

I was carried from the field so shrouded in pain that my mind could not leave that site in my guts where the sudden torment of a crushed testicle had drawn it. I literally did not know or care where I was. The ball was advanced fifteen yards for the late hit, but that too meant nothing to me as ice was applied and the team physician, not realizing the extent of the injury, advised me to breathe deeply.

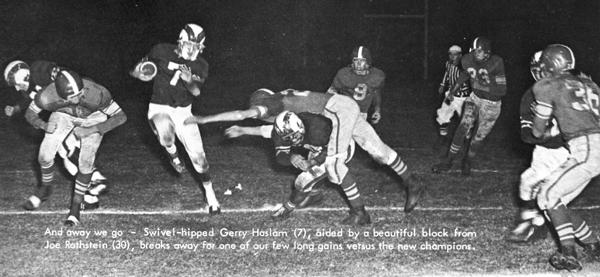

Eventually pain began to subside and I was able to walk, then jog, on the sideline. We were behind 0-7 in the final quarter and driving deep into our opponent's territory. But we were running out of chances; it was fourth down and we needed a long five yards for a first. "Haslam," coach Marv Mosconi asked, "can you play? We need you to run a power sweep."

He was the coach and he needed me to run a sweep, so I ran it, but gained only a short five when our end could not handle his man and I was forced to veer toward their safety to avoid charging linemen. Neither team scored thereafter, so we lost the game and the title.

Thirty years later, I was playing with one of my children when his foot accidently caught my damaged testicle and I again collapsed. Despite two succeeding years of therapy, the ruined organ could not be saved. I was by then thoughtful about many things and I could not miss the irony: the sport that had to a great degree given validation to my early manhood had now cost me a chunk of it.

I was low about that orchiectomy, moping and uncertain that my sexual vigor would remain unabated. Middle age had been a time of gradual physical diminution: a ruptured disk had, for example, forced me to stop competitive running when I was 41. Now a deeper threat was posed. Where was this old warrior's healing ceremony? It was, of course, within me, for all ceremonies actually function to concentrate and release the power within.

Two of my closest friends, both ex-college football players, began immediate shamanism, via negativa in the manner of males. Jim Gray, a physiologist said, among many other things, "Man, that must be a record for micro-micro surgery, little white dude like you. Hey, you might make The Guinness Book of World Records." One of chemist Gene Schaumberg's contributions included this prediction: "Let's see, given your normal level of sexual activity, it'll be a couple of years before you'll be due to find out if what's left of your equipment still works."

Well, I didn't wait that long. The doctor recommended two weeks of abstinence, but it wasn't his ball that had been carved away. The second day home, I affirmed that football had not destroyed what it had once symbolically bestowed.

The warrior tradition is one of many paths to manhood, and there are many ways to become a warrior — actual combat being the apotheosis. I chose the one most accessible during my adolescence: Football, with its rituals (the music, the attire, the incantations), its secrets (which I'm not telling), its priests (the coaches) and oracles (the press), was quasi-religious in a society that had lost much of its sacrality.

More than that, it was a sport that forced me beyond my assumed capabilities, teaching me that life wasn't supposed to be only sweetness and ease. In so doing, it prepared me for inevitable losses — even of that small orb of amorous tissue I so miss. In truth, though, I've suffered far more devastating damage to parts of me that cannot be cut, and I've survived. Most of all, I learned that perfection — going unbeaten in life — is a an admirable goal but an unrealistic expectation. But I've also learned that not to try — not to go balls out, as we used to say — is itself a betrayal.

My class lost six games in our four years of high school football. The worst defeat we suffered was 22-8 at the hands of one of the California's top teams, San Joaquin Memorial of Fresno, in 1954. Ironically, I played one of my better games that night, gaining 113 yards in 20 carries and patrolling as safety on defense. Near the end of the contest, an All-State linebacker named Larry Snyder, who would soon be starting for USC, barreled me into his team's bench as I tried to cut-back on a sweep. As I untangled myself from various Panthers, Snyder grabbed my shoulder pads and jerked me to my feet. He outweighed me by at least 50 lbs. and was an immeasurably more gifted athlete but, thinking he wanted to fight, I thrust my thin chest against his.

"Nice run, guy," he grinned, and he slapped my helmet.

|

Bloodrites appeared in Coming of Age in California, published by Devil Mountain Books in 1990. Devil Mountain Books is no longer in business; but copies of Coming of Age in California are available on Amazon as either the original book [Click Here!], or as an eBook [Click Here!]. |